Gas misconceptions cause billions in industrial losses annually. Engineers often treat gases like liquids or solids, leading to catastrophic system failures and safety hazards. Understanding fundamental gas concepts prevents costly mistakes and optimizes system performance.

Gas is a state of matter characterized by molecules in constant random motion with negligible intermolecular forces1, filling any container completely while exhibiting compressible behavior governed by pressure, volume, and temperature relationships.

Last year, I consulted for a German chemical engineer named Klaus Mueller whose reactor system kept failing due to unexpected pressure surges. His team was applying liquid-based calculations to gas systems. After explaining fundamental gas concepts and implementing proper gas behavior models, we eliminated pressure fluctuations and increased process efficiency by 42%.

Table of Contents

- What Defines Gas as a State of Matter?

- How Do Gas Molecules Behave at the Microscopic Level?

- What Are the Fundamental Properties of Gases?

- How Do Pressure, Volume, and Temperature Interact in Gases?

- What Are the Different Types of Gases in Industrial Applications?

- How Do Gas Laws Govern Industrial Gas Behavior?

- Conclusion

- FAQs About Basic Gas Concepts

What Defines Gas as a State of Matter?

Gas represents one of the fundamental states of matter, distinguished by unique molecular arrangements and behaviors that differentiate it from solids and liquids.

Gas is defined by molecules in continuous random motion with minimal intermolecular attractions, allowing complete expansion to fill any container while maintaining compressible properties and low density compared to liquids and solids.

Molecular Arrangement Characteristics

Gas molecules exist in a highly disordered state with maximum freedom of movement, creating unique physical and chemical properties.

Key Molecular Features:

| Characteristic | Gas State | Liquid State | Solid State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Spacing | Very large (10x diameter) | Small (1x diameter) | Fixed positions |

| Molecular Motion | Random, high velocity | Random, restricted | Vibrational only |

| Intermolecular Forces | Negligible | Moderate | Strong |

| Shape | No fixed shape | No fixed shape | Fixed shape |

| Volume | Fills container | Fixed volume | Fixed volume |

Compressibility Properties

Unlike solids and liquids, gases exhibit significant compressibility due to large intermolecular spaces that can be reduced under pressure.

Compressibility Comparison:

- Gases: Highly compressible (volume changes significantly with pressure)

- Liquids: Slightly compressible (minimal volume change)

- Solids: Nearly incompressible (negligible volume change)

Compressibility Factor2: Z = PV/(nRT)

- Z ≈ 1 for ideal gases

- Z < 1 for real gases at high pressure

- Z > 1 for real gases at very high pressure

Density Characteristics

Gas density is significantly lower than liquids or solids due to large intermolecular spacing and varies dramatically with pressure and temperature.

Density Relationships:

- Gas Density: 0.001-0.01 g/cm³ (at standard conditions)

- Liquid Density: 0.5-2.0 g/cm³ (typical range)

- Solid Density: 1-20 g/cm³ (typical range)

Gas Density Formula: ρ = PM/(RT)

Where:

- P = Pressure

- M = Molecular weight

- R = Universal gas constant

- T = Absolute temperature

Expansion and Contraction Behavior

Gases exhibit dramatic expansion and contraction with temperature and pressure changes, following predictable thermodynamic relationships.

Expansion Characteristics:

- Thermal Expansion: Significant volume increase with temperature

- Pressure Response: Volume inversely proportional to pressure

- Unlimited Expansion: Will fill any available space

- Rapid Equilibration: Quickly reaches uniform conditions

How Do Gas Molecules Behave at the Microscopic Level?

Gas molecular behavior follows kinetic theory principles that explain macroscopic gas properties through microscopic molecular motion and interactions.

Gas molecules exhibit random translational motion with velocities following Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, experiencing elastic collisions while maintaining average kinetic energy proportional to absolute temperature.

Kinetic Theory3 Fundamentals

Kinetic molecular theory provides the foundation for understanding gas behavior through molecular motion principles.

Basic Kinetic Theory Assumptions:

- Point Particles: Gas molecules have negligible volume

- Random Motion: Molecules move in straight lines until collision

- Elastic Collisions: No energy loss during molecular collisions

- No Intermolecular Forces: Except during brief collisions

- Temperature Relationship: Average kinetic energy ∝ absolute temperature

Molecular Velocity Distribution

Gas molecules exhibit a range of velocities following the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, with most molecules near the average velocity.

Velocity Distribution Parameters:

- Most Probable Velocity: vₘₚ = √(2RT/M)

- Average Velocity: v̄ = √(8RT/πM)

- Root Mean Square Velocity: vᵣₘₛ = √(3RT/M)

Where:

- R = Universal gas constant

- T = Absolute temperature

- M = Molecular weight

Temperature Effects on Velocity:

| Temperature | Average Velocity (m/s) | Molecular Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 273 K (0°C) | 461 (air molecules) | Moderate motion |

| 373 K (100°C) | 540 (air molecules) | Increased motion |

| 573 K (300°C) | 668 (air molecules) | High-energy motion |

Collision Frequency and Mean Free Path

Gas molecules constantly collide with each other and container walls, determining pressure and transport properties.

Collision Characteristics:

Mean Free Path: λ = 1/(√2 × n × σ)

Where:

- n = Number density of molecules

- σ = Collision cross-section

Collision Frequency: ν = v̄/λ

Typical Values at Standard Conditions:

- Mean Free Path: 68 nm (air at STP)

- Collision Frequency: 7 × 10⁹ collisions/second

- Wall Collision Rate: 2.7 × 10²³ collisions/cm²·s

Energy Distribution Among Molecules

Gas molecules possess kinetic energy distributed according to temperature, with higher temperatures creating broader energy distributions.

Energy Components:

- Translational Energy: ½mv² (motion through space)

- Rotational Energy: ½Iω² (molecular rotation)

- Vibrational Energy: Potential + kinetic (molecular vibration)

Average Translational Energy: Eₜᵣₐₙₛ = (3/2)kT

Where k = Boltzmann constant

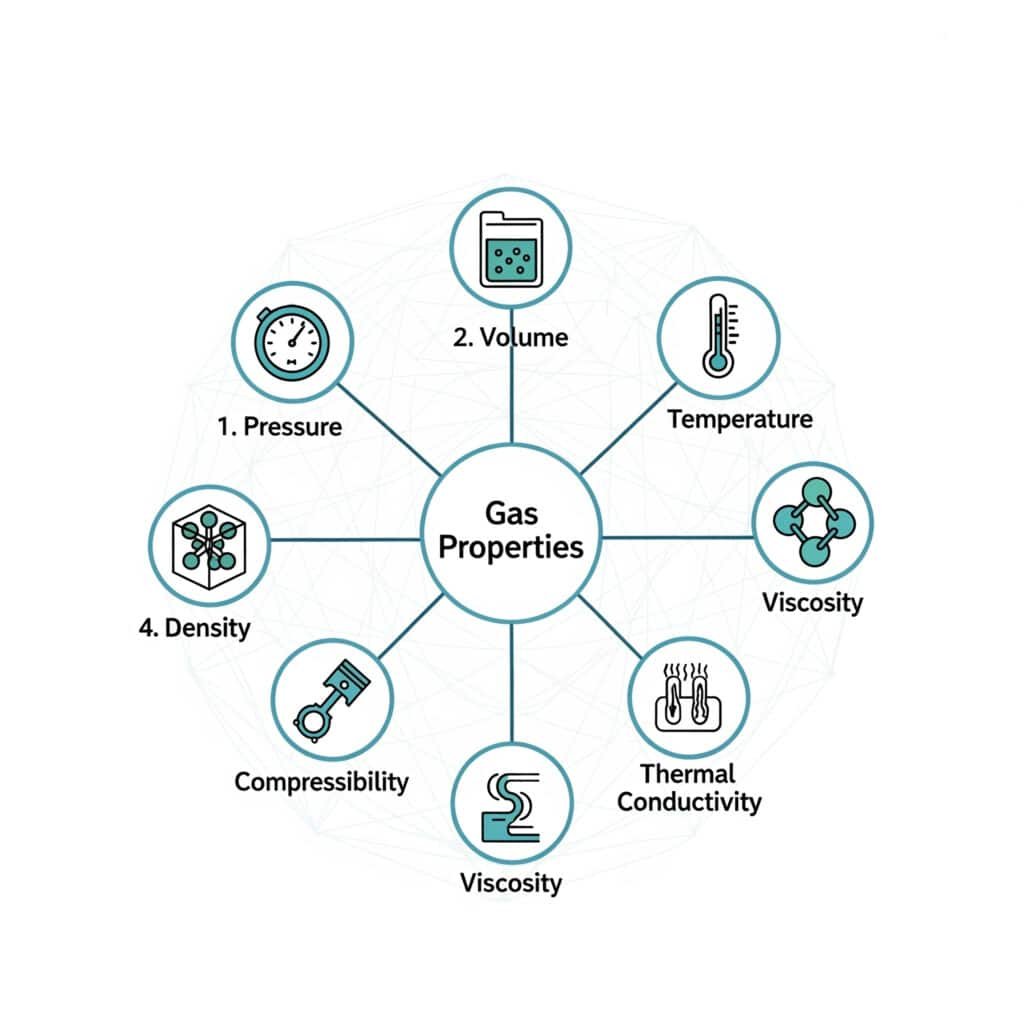

What Are the Fundamental Properties of Gases?

Gases exhibit unique properties that distinguish them from other states of matter and determine their behavior in industrial applications.

Fundamental gas properties include pressure, volume, temperature, density, compressibility, viscosity, and thermal conductivity, all interconnected through thermodynamic relationships and molecular behavior.

Pressure Properties

Gas pressure results from molecular collisions with container walls, creating force per unit area that varies with molecular density and velocity.

Pressure Characteristics:

- Origin: Molecular collisions with surfaces

- Units: Pascal (Pa), atmosphere (atm), PSI

- Measurement: Absolute vs. gauge pressure

- Variation: Changes with temperature and volume

Pressure Relationships:

Kinetic Theory Pressure: P = (1/3)nmv̄²

Where:

- n = Number density

- m = Molecular mass

- v̄² = Mean square velocity

Volume Properties

Gas volume represents the space occupied by molecules, including both molecular volume and intermolecular space.

Volume Characteristics:

- Container Dependent: Gas fills available space completely

- Compressible: Volume changes significantly with pressure

- Temperature Sensitive: Expands with increasing temperature

- Molar Volume: Volume per mole at standard conditions

Standard Conditions:

- STP (Standard Temperature and Pressure): 0°C, 1 atm

- Molar Volume at STP: 22.4 L/mol for ideal gas

- SATP (Standard Ambient): 25°C, 1 bar

Temperature Properties

Temperature measures average molecular kinetic energy and determines gas behavior through thermodynamic relationships.

Temperature Effects:

| Property | Temperature Increase Effect | Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Velocity | Increases | v ∝ √T |

| Pressure (constant V) | Increases | P ∝ T |

| Volume (constant P) | Increases | V ∝ T |

| Density (constant P) | Decreases | ρ ∝ 1/T |

Density and Specific Volume

Gas density varies significantly with pressure and temperature, making it a critical property for industrial calculations.

Density Relationships:

Ideal Gas Density: ρ = PM/(RT)

Specific Volume: v = 1/ρ = RT/(PM)

Density Variations:

- Pressure Effect: Density increases linearly with pressure

- Temperature Effect: Density decreases with temperature

- Molecular Weight Effect: Heavier gases have higher density

- Altitude Effect: Density decreases with elevation

Viscosity Properties

Gas viscosity determines resistance to flow and affects heat and mass transfer in industrial processes.

Viscosity Characteristics:

- Temperature Dependence: Increases with temperature (unlike liquids)

- Pressure Independence: Minimal effect at moderate pressures

- Molecular Origin: Momentum transfer between gas layers

- Measurement Units: Pa·s, cP (centipoise)

Viscosity Temperature Relationship:

Sutherland’s Formula: μ = μ₀(T/T₀)^(3/2) × (T₀ + S)/(T + S)

Where S is Sutherland’s constant

Thermal Conductivity

Gas thermal conductivity determines heat transfer capability and varies with temperature and molecular properties.

Thermal Conductivity Features:

- Molecular Mechanism: Energy transfer through molecular collisions

- Temperature Dependence: Generally increases with temperature

- Pressure Independence: Constant at moderate pressures

- Gas Type Dependence: Varies with molecular weight and structure

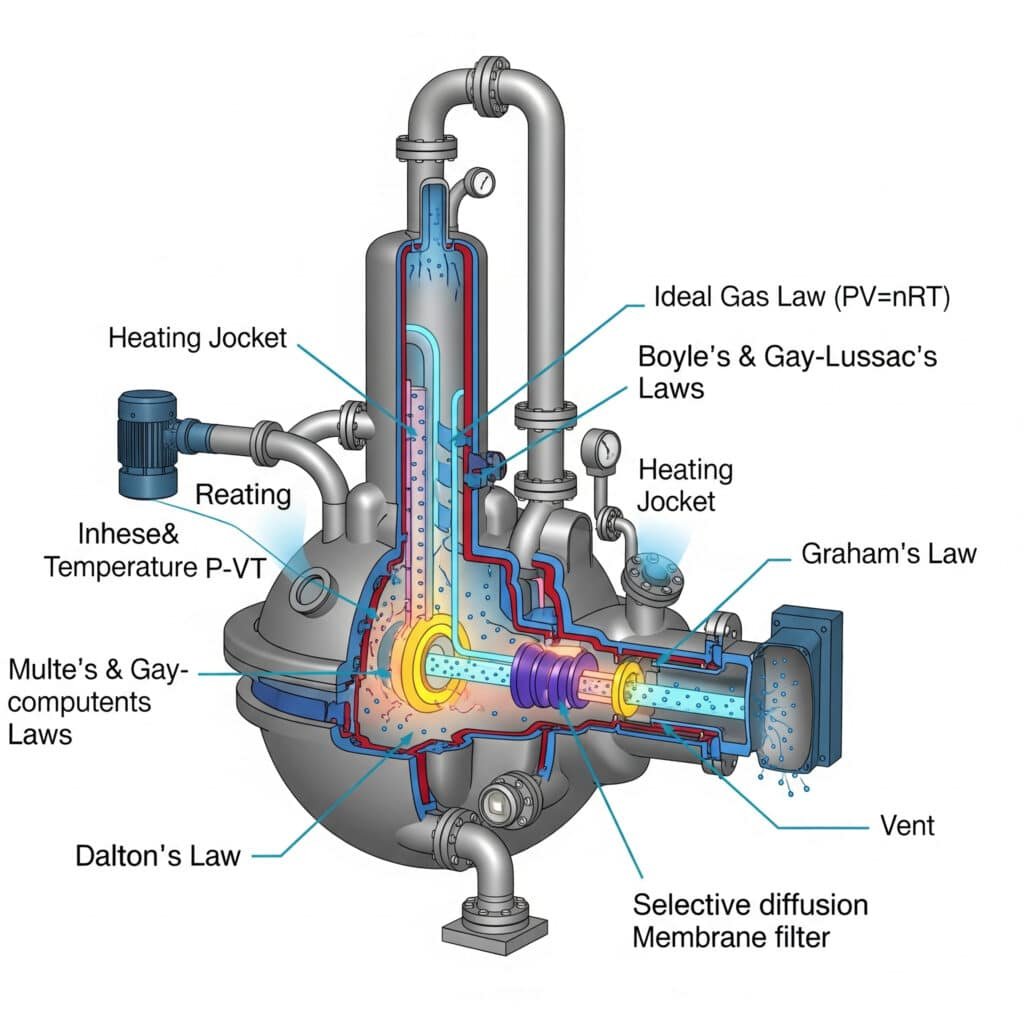

How Do Pressure, Volume, and Temperature Interact in Gases?

The interaction between pressure, volume, and temperature in gases follows fundamental thermodynamic relationships that govern all gas behavior in industrial applications.

Gas pressure, volume, and temperature are interconnected through the ideal gas law4 PV = nRT, where changes in any property affect the others according to specific thermodynamic processes and constraints.

Ideal Gas Law Relationships

The ideal gas law provides the fundamental relationship between gas properties, serving as the foundation for most gas calculations.

Ideal Gas Law Forms:

PV = nRT (molar form)

PV = mRT/M (mass form)

P = ρRT/M (density form)

Where:

- P = Absolute pressure

- V = Volume

- n = Number of moles

- R = Universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K)

- T = Absolute temperature

- m = Mass

- M = Molecular weight

- ρ = Density

Constant Property Processes

Gas behavior depends on which properties remain constant during thermodynamic processes.

Process Types and Relationships:

| Process | Constant Property | Relationship | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal | Temperature | PV = constant | Slow compression/expansion |

| Isobaric | Pressure | V/T = constant | Heating at constant pressure |

| Isochoric | Volume | P/T = constant | Heating in rigid container |

| Adiabatic | No heat transfer | PV^γ = constant | Rapid compression/expansion |

Combined Gas Law

When mass remains constant but multiple properties change, the combined gas law applies.

Combined Gas Law Formula:

(P₁V₁)/T₁ = (P₂V₂)/T₂

This relationship is essential for:

- Gas storage calculations

- Pipeline design

- Process equipment sizing

- Safety system design

Real Gas Deviations

Real gases deviate from ideal behavior under certain conditions, requiring correction factors or alternative equations of state.

Deviation Conditions:

- High Pressure: Molecular volume becomes significant

- Low Temperature: Intermolecular forces become important

- Near Critical Point: Phase change effects occur

- Polar Molecules: Electrical interactions affect behavior

Compressibility Factor Correction:

PV = ZnRT

Where Z is the compressibility factor accounting for real gas behavior.

I recently helped a French process engineer named Marie Dubois in Lyon whose gas storage system experienced unexpected pressure variations. By properly accounting for real gas behavior using compressibility factors, we improved pressure prediction accuracy by 95% and eliminated safety concerns.

What Are the Different Types of Gases in Industrial Applications?

Industrial applications utilize various gas types, each with unique properties and behaviors that determine their suitability for specific processes and applications.

Industrial gases include inert gases (nitrogen, argon), reactive gases (oxygen, hydrogen), fuel gases (natural gas, propane), and specialty gases (helium, carbon dioxide), each requiring specific handling and safety considerations.

Inert Gases

Inert gases resist chemical reactions, making them ideal for protective atmospheres and safety applications.

Common Inert Gases:

| Gas | Chemical Formula | Key Properties | Industrial Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen | N₂ | Non-reactive, abundant | Blanketing, purging, packaging |

| Argon | Ar | Dense, chemically inert | Welding, metal processing |

| Helium | He | Light, inert, low boiling point | Leak testing, cooling |

| Neon | Ne | Inert, distinctive glow | Lighting, lasers |

Inert Gas Applications:

- Atmosphere Protection: Prevent oxidation and contamination

- Fire Suppression: Displace oxygen to prevent combustion

- Process Blanketing: Maintain inert environment

- Quality Control: Prevent chemical reactions during storage

Reactive Gases

Reactive gases participate in chemical processes and require careful handling due to their chemical activity.

Major Reactive Gases:

- Oxygen (O₂): Supports combustion, oxidation processes

- Hydrogen (H₂): Fuel gas, reducing agent, high energy density

- Chlorine (Cl₂): Chemical processing, water treatment

- Ammonia (NH₃): Fertilizer production, refrigeration

Safety Considerations:

- Combustibility: Many reactive gases are flammable or explosive

- Toxicity: Some gases are harmful or lethal in small concentrations

- Corrosivity: Chemical reactions can damage equipment

- Reactivity: Unexpected reactions with other materials

Fuel Gases

Fuel gases provide energy through combustion processes in heating, power generation, and industrial processes.

Common Fuel Gases:

| Fuel Gas | Heating Value (BTU/ft³) | Flame Temperature (°F) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Gas | 1000-1100 | 3600 | Heating, power generation |

| Propane | 2500 | 3600 | Portable heating, cutting |

| Acetylene | 1500 | 6300 | Welding, cutting |

| Hydrogen | 325 | 4000 | Clean fuel, processing |

Specialty Gases

Specialty gases serve specific industrial applications requiring precise composition and purity levels.

Specialty Gas Categories:

- Ultra-High Purity: >99.999% purity for semiconductor manufacturing

- Calibration Gases: Precise mixtures for instrument calibration

- Medical Gases: Pharmaceutical and healthcare applications

- Research Gases: Scientific and laboratory applications

Gas Mixtures

Many industrial applications use gas mixtures to achieve specific properties or performance characteristics.

Common Gas Mixtures:

- Air: 78% N₂, 21% O₂, 1% other gases

- Shielding Gas: Argon + CO₂ for welding

- Breathing Gas: Oxygen + nitrogen for diving

- Calibration Gas: Precise mixtures for testing

How Do Gas Laws Govern Industrial Gas Behavior?

Gas laws provide the mathematical framework for predicting and controlling gas behavior in industrial systems, enabling safe and efficient process design.

Gas laws including Boyle’s Law, Charles’s Law, Gay-Lussac’s Law, and Avogadro’s Law combine to form the ideal gas law, while specialized laws like Dalton’s Law5 and Graham’s Law govern gas mixtures and transport properties.

Boyle’s Law Applications

Boyle’s Law describes the inverse relationship between pressure and volume at constant temperature, fundamental to compression and expansion processes.

Boyle’s Law: P₁V₁ = P₂V₂ (at constant T)

Industrial Applications:

- Gas Compression: Calculate compression ratios and power requirements

- Storage Systems: Determine storage capacity at different pressures

- Pneumatic Systems: Design actuators and control systems

- Vacuum Systems: Calculate pumping requirements

Compression Work Calculation:

Work = P₁V₁ ln(V₁/V₂) (isothermal process)

Charles’s Law Applications

Charles’s Law governs volume-temperature relationships at constant pressure, critical for thermal expansion calculations.

Charles’s Law: V₁/T₁ = V₂/T₂ (at constant P)

Industrial Applications:

- Thermal Expansion: Account for volume changes with temperature

- Heat Exchangers: Calculate gas volume changes

- Safety Systems: Design for thermal expansion effects

- Process Control: Temperature-based volume corrections

Gay-Lussac’s Law Applications

Gay-Lussac’s Law relates pressure and temperature at constant volume, essential for pressure vessel and safety system design.

Gay-Lussac’s Law: P₁/T₁ = P₂/T₂ (at constant V)

Industrial Applications:

- Pressure Vessel Design: Calculate pressure increases with temperature

- Safety Relief Systems: Size relief valves for thermal effects

- Gas Storage: Account for pressure variations with temperature

- Process Safety: Prevent overpressure from heating

Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures

Dalton’s Law governs gas mixture behavior, essential for processes involving multiple gas components.

Dalton’s Law: P_total = P₁ + P₂ + P₃ + … + Pₙ

Partial Pressure Calculation:

Pᵢ = (nᵢ/n_total) × P_total = xᵢ × P_total

Where xᵢ is the mole fraction of component i

Applications:

- Gas Separation: Design separation processes

- Combustion Analysis: Calculate air-fuel ratios

- Environmental Monitoring: Analyze gas concentrations

- Quality Control: Monitor gas purity

Graham’s Law of Effusion

Graham’s Law describes gas diffusion and effusion rates based on molecular weight differences.

Graham’s Law: r₁/r₂ = √(M₂/M₁)

Where r is the effusion rate and M is molecular weight

Industrial Applications:

- Gas Separation: Design membrane separation systems

- Leak Detection: Predict gas escape rates

- Mixing Processes: Calculate mixing times

- Mass Transfer: Design gas absorption systems

Avogadro’s Law Applications

Avogadro’s Law relates volume to the amount of gas at constant temperature and pressure.

Avogadro’s Law: V₁/n₁ = V₂/n₂ (at constant T and P)

Applications:

- Stoichiometric Calculations: Chemical reaction volumes

- Gas Metering: Flow rate measurements

- Process Design: Reactor sizing calculations

- Quality Control: Concentration measurements

I recently worked with an Italian chemical engineer named Giuseppe Romano in Milan whose gas mixing system produced inconsistent results. By applying Dalton’s Law and proper partial pressure calculations, we achieved ±0.1% mixing accuracy and eliminated product quality issues.

Conclusion

Gas represents a fundamental state of matter characterized by molecular motion, compressible behavior, and pressure-volume-temperature relationships governed by thermodynamic laws that determine industrial gas applications and safety requirements.

FAQs About Basic Gas Concepts

What is the basic definition of gas?

Gas is a state of matter where molecules are in constant random motion with negligible intermolecular forces, completely filling any container while exhibiting compressible behavior governed by pressure, volume, and temperature relationships.

How do gas molecules move and behave?

Gas molecules move randomly in straight lines until collisions occur, with velocities following Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution and average kinetic energy proportional to absolute temperature according to kinetic molecular theory.

What makes gases different from liquids and solids?

Gases have much larger intermolecular spacing, negligible intermolecular forces, high compressibility, low density, and ability to completely fill any container, unlike the fixed arrangements in solids and liquids.

What is the ideal gas law and why is it important?

The ideal gas law (PV = nRT) relates pressure, volume, temperature, and amount of gas, providing the fundamental equation for gas calculations in industrial applications and process design.

How do pressure, volume, and temperature affect each other in gases?

Gas pressure, volume, and temperature are interconnected through thermodynamic relationships where changes in one property affect the others according to specific process constraints (isothermal, isobaric, isochoric, or adiabatic).

What are the main types of industrial gases?

Industrial gases include inert gases (nitrogen, argon), reactive gases (oxygen, hydrogen), fuel gases (natural gas, propane), and specialty gases (helium, CO₂), each with specific properties and safety requirements.

-

Provides a detailed explanation of intermolecular forces (such as van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds), which are the attractions or repulsions between neighboring molecules that determine a substance’s physical properties and state of matter. ↩

-

Explains the concept of the Compressibility Factor (Z), a correction factor used in thermodynamics to account for the deviation of a real gas from ideal gas behavior, which is crucial for accurate calculations at high pressures or low temperatures. ↩

-

Offers an overview of the kinetic theory of gases, a scientific model that explains the macroscopic properties of gases (like pressure and temperature) by considering the random motion and collisions of their constituent molecules. ↩

-

Describes the ideal gas law (PV=nRT), the fundamental equation of state that approximates the behavior of most gases under various conditions by relating their pressure, volume, temperature, and amount. ↩

-

Details Dalton’s Law, which states that in a mixture of non-reacting gases, the total pressure exerted is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the individual gases, a fundamental principle for handling gas mixtures. ↩