Introduction

Your pneumatic system is mysteriously losing pressure overnight, but there are no visible leaks. 🔍 You’ve checked every fitting, replaced suspect seals, and pressure-tested the lines—yet every morning, the system needs repressurization. The invisible culprit? Gas permeation through seal materials, a molecular-level phenomenon that silently drains efficiency and increases operating costs by 15-30% in many industrial systems.

Gas permeation is the molecular diffusion of compressed air through the polymer matrix of seal materials at rates determined by material chemistry, gas type, pressure differential, temperature, and seal thickness—permeation rates ranging from 0.5-50 cm³/(cm²·day·atm) cause gradual pressure loss even in perfectly installed seals, making material selection critical for applications requiring extended pressure holding, minimal air consumption, or operation with specialty gases like nitrogen or helium.

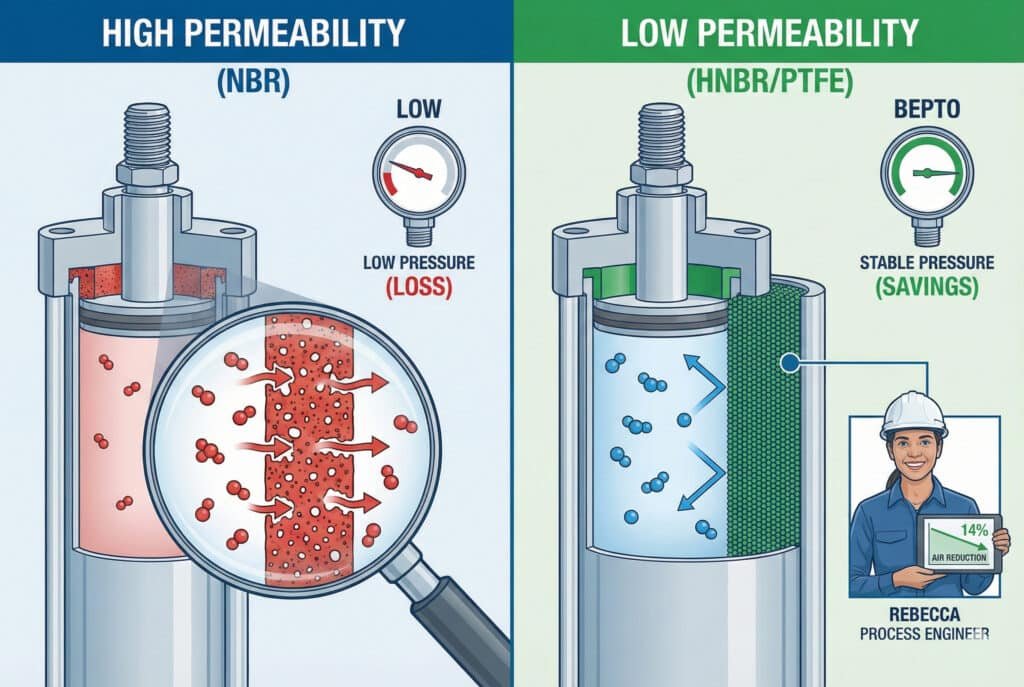

Last year, I worked with Rebecca, a process engineer at a pharmaceutical packaging facility in Massachusetts, who was frustrated by unexplained compressed air consumption increases. Her system used 18% more air than design specifications, costing over $12,000 annually in wasted compressor energy. After analyzing her cylinder seal materials, we discovered high-permeability NBR seals were the problem. Switching to low-permeability Bepto cylinders with HNBR and PTFE seal systems reduced her air consumption by 14% and paid for itself in seven months. 💰

Table of Contents

- What Is Gas Permeation and How Does It Differ from Leakage?

- How Do Different Seal Materials Compare in Gas Permeation Rates?

- What Factors Influence Permeation Rates in Pneumatic Cylinder Applications?

- Which Seal Materials Minimize Permeation for Critical Applications?

What Is Gas Permeation and How Does It Differ from Leakage?

Understanding the molecular physics of permeation helps you diagnose mysterious pressure losses and select appropriate seal materials. 🔬

Gas permeation is a three-step molecular process where gas molecules dissolve into the seal material surface, diffuse through the polymer matrix driven by concentration gradients, and desorb on the low-pressure side—unlike mechanical leakage through gaps or defects, permeation occurs through intact material at rates governed by the permeability coefficient (product of solubility and diffusivity), making it unavoidable but controllable through material selection and seal geometry optimization.

The Molecular Mechanism of Permeation

Think of seal materials as molecular sponges with microscopic spaces between polymer chains. Gas molecules, despite being “sealed,” can actually dissolve into the material surface, wiggle through these spaces, and emerge on the other side. This isn’t a defect—it’s fundamental physics that occurs in all elastomers and polymers.

The process follows Fick’s laws of diffusion1. The permeation rate is proportional to the pressure difference across the seal and inversely proportional to seal thickness. This means doubling the pressure doubles the permeation rate, while doubling the seal thickness cuts it in half.

Permeation vs. Leakage: Critical Distinctions

Many engineers confuse these phenomena, but they’re fundamentally different:

Mechanical Leakage:

- Occurs through physical gaps, scratches, or damage

- Flow rate follows pressure to the 0.5-1.0 power (depending on flow regime)

- Can be detected with soap solution or ultrasonic leak detectors2

- Eliminated by proper installation and seal replacement

- Typically measured in liters/minute

Molecular Permeation:

- Occurs through intact material structure

- Flow rate is linear with pressure (first-order process)

- Cannot be detected by conventional leak detection methods

- Inherent to material choice, only reduced by material selection

- Typically measured in cm³/(cm²·day·atm) or similar units

At Bepto, we’ve investigated hundreds of “mysterious leak” cases where customers insisted seals were defective. In about 40% of cases, the issue was actually permeation, not leakage—the seals were functioning perfectly, but the material permeability was too high for the application requirements.

Why Permeation Matters in Industrial Pneumatics

For a typical 63mm bore cylinder with 400mm stroke operating at 8 bar, permeation through standard NBR seals can lose 50-150 cm³ of air per day. That might not sound like much, but across 100 cylinders running 24/7, it’s 5-15 liters per day—translating to 1,800-5,500 liters annually per cylinder.

At $0.02-0.04 per cubic meter for compressed air (including compressor energy, maintenance, and system costs), permeation losses can cost $360-2,200 annually per 100-cylinder system. For large facilities with thousands of cylinders, this becomes a significant operational expense that’s completely invisible on maintenance reports.

Time Constants and Pressure Decay Profiles

Permeation creates characteristic pressure decay curves that differ from leakage. Mechanical leaks cause exponential pressure decay that’s rapid initially and slows over time. Permeation causes nearly linear pressure decay after an initial equilibration period.

If you pressurize a cylinder to 8 bar and monitor pressure over 24 hours, you can distinguish the mechanisms:

- Sharp drop in first hour, then stable: Mechanical leakage

- Steady, linear decline: Permeation dominant

- Combination of both: Mixed leakage and permeation

This diagnostic approach has helped me troubleshoot countless customer issues and identify whether seal replacement or material upgrade is the appropriate solution.

How Do Different Seal Materials Compare in Gas Permeation Rates?

Material chemistry fundamentally determines permeation performance, making selection critical for efficiency and cost control. 📊

Seal material permeation rates for compressed air vary by orders of magnitude: PTFE offers the lowest permeation at 0.5-2 cm³/(cm²·day·atm), followed by Viton/FKM at 2-5, HNBR at 5-12, standard polyurethane at 15-25, and NBR at 25-50 cm³/(cm²·day·atm)—these differences translate to 10-100x variation in air loss rates, making material selection the primary factor in minimizing permeation-related operating costs in pneumatic systems.

Comprehensive Material Permeation Comparison

At Bepto, we’ve conducted extensive permeation testing on all seal materials we use. Here’s our measured data for compressed air (primarily nitrogen and oxygen) at 23°C:

| Seal Material | Permeation Rate* | Relative Performance | Cost Factor | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTFE (Virgin) | 0.5-2 | Excellent (1x baseline) | 3.5-4.0x | Critical holding, specialty gases |

| Filled PTFE | 1-3 | Excellent | 2.5-3.0x | High-pressure, low-permeation |

| Viton (FKM) | 2-5 | Very Good | 2.8-3.5x | Chemical resistance + low permeation |

| HNBR | 5-12 | Good | 1.8-2.2x | Balanced performance, oil resistance |

| Polyurethane (AU) | 15-25 | Moderate | 1.0-1.2x | Standard pneumatics, good wear |

| NBR (Nitrile) | 25-50 | Poor | 0.8-1.0x | Low-pressure, cost-sensitive |

| Silicone | 80-150 | Very Poor | 1.2-1.5x | Avoid for pneumatics (high permeation) |

*Units: cm³/(cm²·day·atm) for air at 23°C

Why These Differences Exist: Polymer Chemistry

The molecular structure of polymers determines how easily gas molecules can dissolve and diffuse through them:

PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene): Extremely tight molecular packing with strong carbon-fluorine bonds creates minimal free volume. Gas molecules find few pathways through the structure, resulting in very low permeation.

Fluoroelastomers (Viton/FKM): Similar fluorine chemistry to PTFE but with more flexible elastomeric structure. Still provides excellent barrier properties while maintaining seal flexibility.

Polyurethane: Moderate polarity and hydrogen bonding create a semi-permeable structure. Good mechanical properties but higher permeation than fluoropolymers.

NBR (Nitrile rubber): Relatively open molecular structure with significant free volume allows easier gas diffusion. Excellent for mechanical sealing but poor barrier properties.

Gas-Specific Permeation Variations

Different gases permeate at vastly different rates through the same material. Small molecules like helium and hydrogen permeate 10-100x faster than nitrogen or oxygen:

Helium permeation (relative to air = 1.0x):

- Through NBR: 15-25x faster

- Through polyurethane: 12-18x faster

- Through PTFE: 8-12x faster

This is why helium leak testing is so sensitive—and why systems using helium or hydrogen require special low-permeability seal materials. I once consulted with a hydrogen fuel cell testing lab where standard polyurethane seals were losing 30% of their hydrogen overnight. Switching to PTFE seals reduced losses to under 3%. 🎈

Temperature Effects on Permeation

Permeation rates increase exponentially with temperature, typically doubling every 20-30°C increase. This follows the Arrhenius equation3—higher temperatures provide more molecular energy for diffusion through the polymer matrix.

For a standard polyurethane seal:

- At 20°C: 20 cm³/(cm²·day·atm)

- At 40°C: 35-40 cm³/(cm²·day·atm)

- At 60°C: 60-75 cm³/(cm²·day·atm)

This temperature sensitivity means that cylinders operating in hot environments (near ovens, in summer outdoor conditions, or in tropical climates) experience significantly higher permeation losses than the same cylinders in climate-controlled facilities.

What Factors Influence Permeation Rates in Pneumatic Cylinder Applications?

Beyond material selection, several design and operational parameters affect actual permeation performance in real-world systems. ⚙️

Permeation rates in pneumatic cylinders are influenced by seal geometry (thickness and surface area), operating pressure (linear relationship), temperature (exponential increase), gas composition (small molecules permeate faster), seal compression (affects effective thickness and density), and aging (degradation increases permeation 20-50% over seal lifetime)—optimizing these factors through proper design and material selection can reduce permeation losses by 60-80% compared to baseline configurations.

Seal Geometry and Effective Thickness

Permeation rate is inversely proportional to seal thickness—the path length gas molecules must travel. A seal twice as thick has half the permeation rate. However, there are practical limits:

Thin seals (1-2mm cross-section):

- Higher permeation rates

- Lower sealing force required

- Better for low-friction applications

- Used in our Bepto low-friction rodless cylinders

Thick seals (3-5mm cross-section):

- Lower permeation rates

- Higher sealing force required

- Better for extended pressure holding

- Used in high-pressure and long-hold applications

The effective thickness also depends on seal compression. A seal compressed 15-20% has slightly higher density and lower permeation than the same seal compressed only 5-10%. This is why proper seal groove design matters—it controls compression and therefore permeation performance.

Pressure Differential Effects

Unlike leakage (which follows power-law relationships), permeation is directly proportional to pressure difference. Double the pressure, double the permeation rate. This linear relationship makes permeation increasingly significant at higher pressures.

For a cylinder with polyurethane seals (20 cm³/(cm²·day·atm) permeability):

- At 4 bar: 80 cm³/(cm²·day) permeation

- At 8 bar: 160 cm³/(cm²·day) permeation

- At 12 bar: 240 cm³/(cm²·day) permeation

This is why we at Bepto recommend low-permeability seal materials (HNBR or PTFE) for applications above 10 bar—the permeation losses at high pressure become economically significant even for moderately permeable materials.

Gas Composition and Molecular Size

Industrial compressed air is typically 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, and 1% other gases. These components permeate at different rates:

Relative permeation rates (nitrogen = 1.0x):

- Helium: 10-20x faster

- Hydrogen: 8-15x faster

- Oxygen: 1.2-1.5x faster

- Nitrogen: 1.0x (baseline)

- Carbon dioxide: 0.8-1.0x

- Argon: 0.6-0.8x

For specialty gas applications—nitrogen blanketing, inert gas handling, or hydrogen systems—this becomes critical. I worked with Daniel, an engineer at a semiconductor manufacturing plant in California, who was using nitrogen-purged cylinders for contamination-sensitive processes. His standard NBR seals were allowing 8-10% nitrogen loss per day, requiring constant purging. We specified Bepto cylinders with Viton seals, reducing nitrogen loss to under 2% daily and cutting his nitrogen costs by $18,000 annually. 💨

Seal Aging and Permeation Degradation

New seals have optimal permeation resistance, but aging degrades performance through several mechanisms:

Compression set4: Permanent deformation reduces effective seal thickness

Oxidation: Chemical degradation creates micro-voids in the polymer

Plasticizer loss: Volatile components evaporate, making material more brittle and porous

Micro-cracking: Cyclic stress creates microscopic surface cracks

In our long-term testing at Bepto, we’ve found that permeation rates increase 20-30% over the first million cycles for polyurethane seals, and 30-50% for NBR seals. PTFE and Viton show minimal degradation—typically under 10% increase even after 5 million cycles.

This aging effect means that systems optimized for new seal performance will gradually lose efficiency. Designing with 30-40% margin above initial permeation rates ensures consistent performance throughout seal life.

Which Seal Materials Minimize Permeation for Critical Applications?

Selecting optimal seal materials requires balancing permeation performance, mechanical properties, cost, and application-specific requirements. 🎯

For critical low-permeation applications, PTFE and filled PTFE compounds offer the best performance with 10-50x lower permeation than standard elastomers, while HNBR provides an excellent cost-performance balance for general industrial use with 2-5x better permeation resistance than polyurethane—application-specific selection should consider operating pressure (PTFE for >12 bar), temperature range (Viton for >80°C), chemical exposure (FKM for oils/solvents), and economic justification based on air consumption costs versus material premium.

PTFE: The Gold Standard for Low Permeation

Virgin PTFE offers unmatched permeation resistance, but it requires careful application engineering. PTFE is not elastic like rubber—it’s a thermoplastic that requires mechanical energization (springs or O-rings) to maintain sealing force.

Advantages:

- Lowest permeation rates (0.5-2 cm³/(cm²·day·atm))

- Excellent chemical resistance (virtually universal)

- Wide temperature range (-200°C to +260°C)

- Very low friction coefficient (0.05-0.10)

Limitations:

- Requires energizer elements (adds complexity)

- Higher initial cost (3-4x standard seals)

- Can cold-flow under sustained high pressure

- Requires precise groove design

At Bepto, we use spring-energized PTFE seals in our premium rodless cylinders for applications requiring extended pressure holding, minimal air consumption, or operation with specialty gases. The 3-4x cost premium is easily justified when permeation losses exceed $500-1,000 annually per cylinder.

HNBR: The Practical Low-Permeation Choice

Hydrogenated nitrile rubber (HNBR) offers an excellent compromise between performance and cost. It’s chemically similar to standard NBR but with saturated polymer chains that provide better heat resistance, ozone resistance, and significantly lower permeation.

Performance characteristics:

- Permeation: 5-12 cm³/(cm²·day·atm) (2-5x better than standard polyurethane)

- Temperature range: -40°C to +150°C

- Excellent oil and fuel resistance

- Good mechanical properties and wear resistance

- Cost premium: 1.8-2.2x standard seals

For most industrial pneumatic applications operating at 8-12 bar, HNBR provides the best overall value. We’ve standardized on HNBR for our Bepto high-pressure cylinder series because it delivers measurable air consumption reduction (typically 8-15%) at a reasonable cost premium that pays back in 12-24 months for most applications.

Application-Based Material Selection Guide

Here’s how we guide customers at Bepto through material selection:

Standard industrial pneumatics (6-10 bar, ambient temperature):

- First choice: Polyurethane (AU) – good all-around performance

- Upgrade option: HNBR – for reduced air consumption

- Premium option: Filled PTFE – for critical applications

High-pressure systems (10-16 bar):

- Minimum: HNBR – necessary for permeation control

- Preferred: Filled PTFE – optimal for pressure holding

- Avoid: Standard NBR or polyurethane (excessive permeation)

Extended pressure holding (>8 hours between cycles):

- Required: PTFE or Viton – minimize overnight pressure loss

- Acceptable: HNBR with oversized seals – increased thickness reduces permeation

- Unacceptable: NBR – will lose 20-40% pressure overnight

Specialty gas applications (nitrogen, helium, hydrogen):

- Required: PTFE – only material with acceptable permeation for small molecules

- Alternative: Viton for nitrogen (acceptable but not optimal)

- Avoid: All standard elastomers (unacceptable permeation rates)

Economic Justification for Low-Permeation Materials

The decision to upgrade seal materials should be based on total cost of ownership, not just initial price. Here’s a real-world calculation I performed for a customer:

System: 50 cylinders, 63mm bore, 8 bar operating pressure, 24/7 operation

Compressed air cost: $0.03/m³ (including energy, maintenance, system costs)

Standard polyurethane seals (20 cm³/(cm²·day·atm)):

- Permeation per cylinder: ~120 cm³/day = 44 liters/year

- Total system: 2,200 liters/year = $66/year

- Seal cost: $8/cylinder = $400 total

HNBR seals (8 cm³/(cm²·day·atm)):

- Permeation per cylinder: ~48 cm³/day = 17.5 liters/year

- Total system: 875 liters/year = $26/year

- Seal cost: $15/cylinder = $750 total

- Annual savings: $40/year, payback: 8.75 years (marginal case)

PTFE seals (1.5 cm³/(cm²·day·atm)):

- Permeation per cylinder: ~9 cm³/day = 3.3 liters/year

- Total system: 165 liters/year = $5/year

- Seal cost: $32/cylinder = $1,600 total

- Annual savings: $61/year, payback: 19.7 years (not justified for this case)

This analysis shows that HNBR might be marginal for this application, while PTFE isn’t economically justified. However, if compressed air costs are higher ($0.05/m³ in some facilities) or pressure is higher (12 bar instead of 8), the economics shift dramatically in favor of low-permeation materials.

I recently helped Maria, a maintenance manager at a food processing plant in Texas, perform this analysis for her 200-cylinder system operating at 12 bar with $0.048/m³ air costs. The HNBR upgrade saved her $4,800 annually with a 6-month payback—a clear win that also reduced her compressor runtime and extended compressor life. 📈

Testing and Verification Methods

When specifying low-permeation seals, demand verification data. At Bepto, we provide permeation test certificates for critical applications using standardized ASTM D14345 testing methods. The test measures gas transmission rate through a seal sample under controlled pressure, temperature, and humidity.

Key test parameters to specify:

- Test gas composition (air, nitrogen, or specific gas)

- Test pressure (should match your operating pressure)

- Test temperature (should match your operating range)

- Sample thickness (should match actual seal dimensions)

Don’t accept generic material data sheets—actual permeation rates can vary 20-40% between different formulations of the “same” material from different suppliers. Verified test data ensures you’re getting the performance you’re paying for.

Conclusion

Gas permeation through seal materials is an invisible but significant source of compressed air waste, energy consumption, and operating costs in pneumatic systems. Understanding permeation mechanisms, material performance differences, and application-specific requirements enables informed material selection that can reduce air losses by 60-80% and deliver measurable ROI through reduced compressor energy and improved system efficiency. At Bepto, we engineer our rodless cylinders with permeation-optimized seal materials because we know that long-term operating costs far exceed initial purchase price—and our customers’ profitability depends on systems that deliver efficient, reliable performance year after year. 🌟

FAQs About Gas Permeation in Pneumatic Seals

Q: How can I determine if my pressure loss is from permeation or mechanical leakage?

Perform a controlled pressure decay test: pressurize the cylinder, isolate it completely, and monitor pressure over 24 hours at constant temperature. Plot pressure versus time—mechanical leakage creates an exponential decay curve (rapid initial drop, then slowing), while permeation creates a linear decay after initial equilibration. At Bepto, we recommend this diagnostic before replacing seals, as it identifies whether material upgrade or seal replacement is the appropriate solution.

Q: Can I reduce permeation by increasing seal compression or using multiple seals?

Increased compression (up to 20-25%) slightly reduces permeation by densifying the material, but excessive compression (>30%) can cause seal damage and actually increase permeation through stress-induced micro-cracking. Multiple seals in series reduce effective permeation by increasing total seal thickness—two 2mm seals provide similar permeation resistance to one 4mm seal, though with higher friction and cost.

Q: Do permeation rates change with seal wear over time?

Yes—permeation typically increases 20-50% over seal lifetime due to compression set (reduced effective thickness), oxidative degradation (increased porosity), and micro-cracking from cyclic stress. This degradation is fastest in the first 500,000 cycles, then stabilizes. PTFE and Viton show minimal degradation (<10% increase), while NBR and polyurethane degrade more significantly (30-50% increase), making low-permeation materials even more cost-effective over long service lives.

Q: Are there coatings or treatments that reduce permeation through standard seal materials?

Surface treatments and barrier coatings have been attempted but generally prove impractical for dynamic seals due to wear and flexing that damages the coating. For static seals (O-rings in end caps), thin PTFE coatings or plasma treatments can reduce permeation 30-50%, but for dynamic piston and rod seals, bulk material selection remains the only reliable approach to controlling permeation in pneumatic cylinder applications.

Q: How do I justify the cost premium of low-permeation seals to management focused on initial purchase price?

Calculate total cost of ownership including compressed air costs over expected seal life (typically 2-5 years)—for a 63mm cylinder at 10 bar with $0.03/m³ air costs, upgrading from polyurethane to HNBR seals saves $15-25 per cylinder annually, providing 12-24 month payback on the material premium. At Bepto, we provide TCO calculation tools that demonstrate how permeation reduction pays for itself through reduced compressor energy, lower maintenance costs, and extended compressor life, making the business case clear and quantifiable for procurement decisions.

-

Learn the fundamental mathematical principles governing the diffusion of gases through solid materials. ↩

-

Learn about the technology used to identify high-frequency sound waves generated by air escaping from pressurized systems. ↩

-

Understand the scientific formula used to calculate the effect of temperature on chemical and physical reaction rates. ↩

-

Discover how permanent deformation affects seal effectiveness and gas barrier performance over time. ↩

-

Review the international standard test method used to determine the gas transmission rate of plastic films and sheeting. ↩