When your pneumatic cylinders suddenly lose 30% of their rated force or fail to achieve specified speeds despite adequate compressor capacity, you’re likely experiencing the cumulative effects of pressure drops across ports and fittings—invisible energy thieves that can reduce system efficiency by 40-60% while remaining completely hidden from casual observation. These pressure losses compound throughout your system, creating performance bottlenecks that frustrate engineers who focus on cylinder sizing while ignoring the critical flow path. 💨

Pressure drop dynamics in pneumatic systems follow fluid mechanics1 principles where each restriction (ports, fittings, valves) creates energy losses proportional to flow velocity squared, with total system pressure drop being the sum of all individual losses, directly reducing available cylinder force and speed performance.

Yesterday, I helped Maria, a manufacturing engineer at a textile machinery plant in Georgia, who discovered that optimizing her pressure drop losses increased her cylinder speeds by 45% without changing a single cylinder or adding compressor capacity.

Table of Contents

- What Causes Pressure Drop in Pneumatic System Components?

- How Do You Calculate and Measure Pressure Losses?

- What Is the Cumulative Impact of Multiple Restrictions?

- How Can You Minimize Pressure Drop for Maximum Performance?

What Causes Pressure Drop in Pneumatic System Components?

Understanding the fundamental mechanisms of pressure drop is essential for system optimization. 🔬

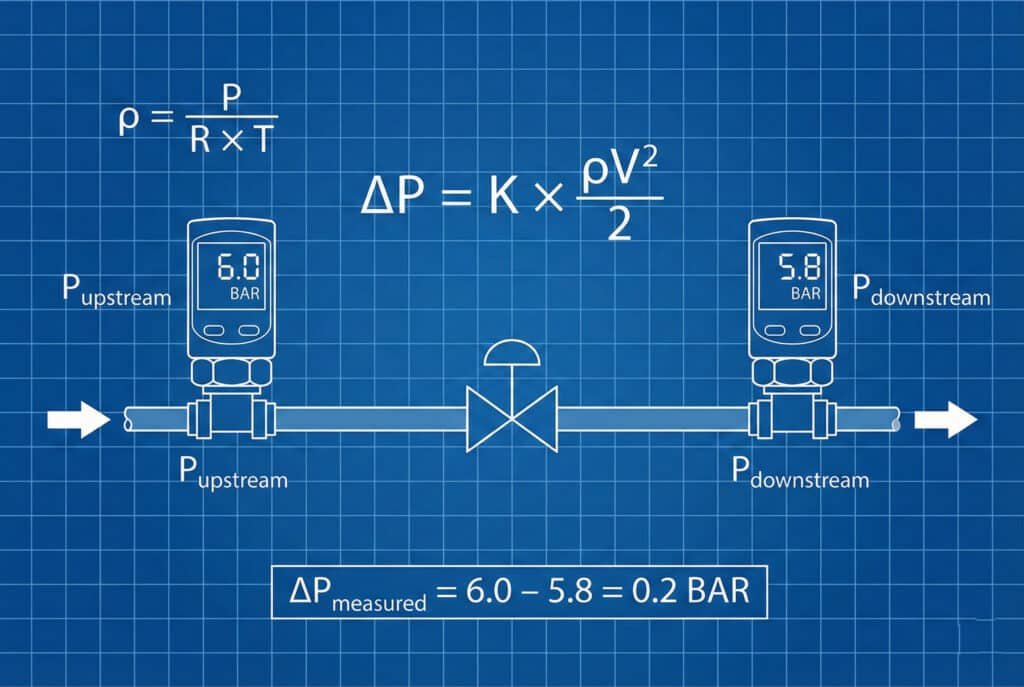

Pressure drop occurs when flowing air encounters restrictions that convert kinetic energy to heat through friction, turbulence, and flow separation2, with losses governed by the equation

\( \Delta P = K \times (\rho V^{2} / 2) \), where K is the loss coefficient specific to each component geometry and flow conditions.

Fundamental Pressure Drop Equation

The basic pressure drop relationship is:

$$

\Delta P = K \times \frac{\rho V^{2}}{2}

$$

Where:

- \( \Delta P \) = Pressure drop (Pa)

- \( K \) = Loss coefficient (dimensionless)

- \( \rho \) = Air density (kg/m^3)

- \( V \) = Air velocity (m/s)

Primary Loss Mechanisms

Friction Losses:

- Wall friction: Air viscosity creates shear stress at pipe walls

- Surface roughness: Irregular surfaces increase friction coefficient

- Length dependency: Losses accumulate over distance

- Reynolds number3 effects: Flow regime affects friction factor

Form Losses:

- Sudden contractions: Flow acceleration through reduced area

- Sudden expansions: Flow deceleration and energy dissipation

- Direction changes: Elbows, tees, and bends create turbulence

- Obstructions: Valves, filters, and fittings interrupt flow

Component-Specific Loss Coefficients

| Component | Typical K Value | Primary Loss Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Straight pipe (per L/D) | 0.02-0.05 | Wall friction |

| 90° elbow | 0.3-0.9 | Flow separation |

| Sudden contraction | 0.1-0.5 | Acceleration losses |

| Sudden expansion | 0.2-1.0 | Deceleration losses |

| Ball valve (full open) | 0.05-0.2 | Minor restriction |

| Gate valve (full open) | 0.1-0.3 | Flow disturbance |

Port Geometry Effects

Cylinder Port Design:

- Sharp-edged ports: High loss coefficients (K = 0.5-1.0)

- Rounded entries: Reduced losses (K = 0.1-0.3)

- Tapered transitions: Minimized separation (K = 0.05-0.15)

- Port diameter: Inverse relationship with velocity and losses

Internal Flow Paths:

- Port depth: Affects entrance and exit losses

- Internal chambers: Create expansion/contraction losses

- Flow direction changes: 90° turns increase losses significantly

- Manufacturing tolerances: Sharp edges vs. smooth transitions

Fitting Contributions

Push-In Fittings:

- Internal restrictions: Reduced effective diameter

- Flow path complexity: Multiple direction changes

- Seal interference: O-rings create flow disturbances

- Assembly variations: Inconsistent internal geometry

Threaded Connections:

- Thread interference: Partial flow obstruction

- Sealant effects: Thread compounds affect flow area

- Alignment issues: Misaligned connections increase losses

- Internal geometry: Varying internal diameters

Case Study: Maria’s Textile Machinery

Maria’s system analysis revealed significant pressure drop sources:

- Supply pressure: 7 bar at compressor

- Cylinder inlet pressure: 4.8 bar (31% loss)

- Major contributors:

– Filters: 0.6 bar loss

– Valve manifold: 0.8 bar loss

– Fittings and tubing: 0.5 bar loss

– Cylinder ports: 0.3 bar loss

This 2.2 bar total pressure drop reduced her effective cylinder force by 31% and speed by 45%.

How Do You Calculate and Measure Pressure Losses?

Accurate pressure drop calculation and measurement enables targeted system optimization. 📊

Calculate pressure losses using component loss coefficients and flow velocities: \( \Delta P = K \times (\rho V^{2} / 2) \), then measure actual losses using high-accuracy pressure transducers positioned before and after each component to validate calculations and identify unexpected restrictions.

Calculation Methodology

Step-by-Step Process:

- Determine flow rate: \( Q = A \times V \) (cylinder requirements)

- Calculate velocities: \( V = Q / A \) for each component

- Find loss coefficients: \( K \) values from literature or testing

- Compute individual losses: \( \Delta P = K \times (\rho V^{2} / 2) \)

- Sum total losses: \( \Delta P_{\text{total}} = \Sigma \Delta P_{\text{individual}} \)

Air Density Calculation:

$$

\rho = \frac{P}{R \times T}

$$

Where:

- \( P \) = Absolute pressure (Pa)

- \( R \) = Specific gas constant4 for air (287 J/kg·K)

- \( T \) = Absolute temperature (K)

Flow Velocity Calculations

For Circular Cross-Sections:

$$

V = \frac{4Q}{\pi D^{2}}

$$

Where:

- \( Q \) = Volumetric flow rate (m^3/s)

- \( D \) = Internal diameter (m)

For Complex Geometries:

$$

V = \frac{Q}{A_{\text{effective}}}

$$

Where \( A_{\text{effective}} \) must be determined experimentally or through CFD analysis5.

Measurement Equipment and Setup

| Equipment | Accuracy | Application | Cost Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential pressure transducers | ±0.1% FS | Component testing | Medium |

| Pitot tubes | ±2% | Velocity measurement | Low |

| Orifice plates | ±1% | Flow rate measurement | Low |

| Mass flow meters | ±0.5% | Precise flow measurement | High |

Measurement Techniques

Pressure Tap Installation:

- Upstream location: 8-10 pipe diameters before restriction

- Downstream location: 4-6 pipe diameters after restriction

- Tap design: Flush-mounted, burr-free holes

- Multiple taps: Average readings for accuracy

Data Collection Protocol:

- Steady-state conditions: Allow system stabilization

- Multiple measurements: Statistical analysis of variations

- Temperature compensation: Correct for density changes

- Flow rate correlation: Measure simultaneous flow and pressure

Calculation Examples

Example 1: Cylinder Port Loss

Given:

- Flow rate: 100 SCFM (0.047 m³/s at standard conditions)

- Port diameter: 8mm

- Operating pressure: 6 bar

- Temperature: 20°C

- Port loss coefficient: K = 0.4

Calculation:

- Velocity: V = 4 × 0.047/(π × 0.008²) = 93.4 m/s

- Density: ρ = 600,000/(287 × 293) = 7.14 kg/m³

- Pressure drop: ΔP = 0.4 × (7.14 × 93.4²)/2 = 12,450 Pa = 0.125 bar

Example 2: Fitting Loss

90° elbow with:

- Internal diameter: 6mm

- Flow rate: 50 SCFM

- Loss coefficient: K = 0.6

Result: \( \Delta P = 0.18\ \text{bar} \)

Validation and Verification

Measurement vs. Calculation:

- Typical agreement: ±15% for standard components

- Complex geometries: ±25% due to geometry uncertainties

- Manufacturing variations: ±10% component-to-component

- Installation effects: ±20% due to upstream/downstream conditions

Sources of Discrepancy:

- Loss coefficient accuracy: Literature values vs. actual components

- Flow regime effects: Transition between laminar and turbulent

- Temperature effects: Density and viscosity variations

- Compressibility: High-speed flow effects

System-Level Analysis

Maria’s Textile System Measurements:

- Calculated total loss: 2.0 bar

- Measured total loss: 2.2 bar (10% difference)

- Major discrepancies:

– Filter housing: 25% higher than calculated

– Valve manifold: 15% higher than expected

– Fittings: Close agreement with calculations

Measurement Insights:

- Filter condition: Partial plugging increased losses

- Manifold design: Internal geometry more restrictive than assumed

- Installation effects: Upstream turbulence affected some measurements

What Is the Cumulative Impact of Multiple Restrictions?

Multiple pressure drops throughout a system create compounding effects that significantly impact performance. 📈

Cumulative pressure drop impact follows the principle that total system loss equals the sum of all individual losses \( \Delta P_{\text{total}} = \Sigma \Delta P_i \), with each restriction reducing available pressure for subsequent components, creating cascading performance degradation that can reduce cylinder force by 40–60% in poorly designed systems.

Series Pressure Drop Analysis

Additive Nature:

$$

\Delta P_{\text{total}} = \Delta P_{1} + \Delta P_{2} + \Delta P_{3} + \cdots + \Delta P_{n}

$$

Each component in the flow path contributes to total system loss.

Available Pressure Calculation:

$$

P_{\text{available}} = P_{\text{supply}} – \Delta P_{\text{total}}

$$

This available pressure determines actual cylinder performance.

Pressure Drop Distribution

Typical System Breakdown:

- Supply system: 10-20% (filters, regulators, main lines)

- Valve manifold: 25-35% (directional valves, flow controls)

- Connecting lines: 15-25% (tubing, fittings)

- Cylinder ports: 10-20% (inlet/outlet restrictions)

- Exhaust system: 5-15% (mufflers, exhaust valves)

Performance Impact Analysis

Force Reduction:

$$

F_{\text{actual}} = F_{\text{rated}} \times \left( \frac{P_{\text{available}}}{P_{\text{rated}}} \right)

$$

Where pressure losses directly reduce available force.

Speed Impact:

Flow rate through restrictions follows:

$$

Q = C_v \times \sqrt{\frac{\Delta P}{SG}}

$$

Reduced available pressure decreases flow rate and cylinder speed.

Cascading Effects

| System Component | Individual Loss | Cumulative Loss | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter | 0.3 bar | 0.3 bar | 4% force reduction |

| Regulator | 0.2 bar | 0.5 bar | 7% force reduction |

| Main valve | 0.6 bar | 1.1 bar | 16% force reduction |

| Fittings | 0.4 bar | 1.5 bar | 21% force reduction |

| Cylinder port | 0.3 bar | 1.8 bar | 26% force reduction |

Non-Linear Effects

Velocity Squared Relationship:

As flow increases, pressure drops increase quadratically:

$$

\Delta P \propto Q^{2}

$$

This means doubling flow rate quadruples pressure drop.

Compounding Restrictions:

Multiple small restrictions can create larger total losses than single large restrictions due to velocity effects.

System Efficiency Analysis

Overall System Efficiency:

$$

\eta_{\text{system}}

= \frac{P_{\text{available}}}{P_{\text{supply}}}

= \frac{P_{\text{supply}} – \Sigma \Delta P}{P_{\text{supply}}}

$$

Energy Waste Calculation:

$$

\eta_{\text{system}}

= \frac{P_{\text{available}}}{P_{\text{supply}}}

= \frac{P_{\text{supply}} – \Sigma \Delta P}{P_{\text{supply}}}

$$

Where wasted energy is converted to heat.

Optimization Priorities

Pareto Analysis:

Focus optimization efforts on components with highest losses:

- Valve manifolds: Often 30-40% of total losses

- Filters: Can be 20-30% when dirty

- Cylinder ports: 15-25% in small bore cylinders

- Fittings: 10-20% cumulative effect

Case Study: Cumulative Impact Assessment

Maria’s System Before Optimization:

- Supply pressure: 7.0 bar

- Available at cylinder: 4.8 bar

- System efficiency: 69%

- Force reduction: 31%

- Speed reduction: 45%

Individual Contributions:

- Primary filter: 0.4 bar (18% of total loss)

- Secondary filter: 0.2 bar (9% of total loss)

- Pressure regulator: 0.3 bar (14% of total loss)

- Main valve manifold: 0.8 bar (36% of total loss)

- Distribution tubing: 0.3 bar (14% of total loss)

- Cylinder connections: 0.2 bar (9% of total loss)

Performance Correlation:

- Theoretical cylinder force: 1,250 N

- Actual measured force: 860 N (31% reduction)

- Correlation accuracy: 98% agreement with pressure-based calculation

How Can You Minimize Pressure Drop for Maximum Performance?

Reducing pressure drop requires systematic optimization of component selection, sizing, and system design. 🎯

Minimize pressure drop through component optimization (larger ports, streamlined valves), system design improvements (shorter paths, fewer restrictions), proper sizing (adequate flow capacity), and maintenance practices (clean filters, proper installation) to recover 80-90% of lost performance.

Component Selection Strategies

Valve Optimization:

- High Cv valves: Select valves with flow coefficients 2-3x calculated requirements

- Full-port designs: Minimize internal restrictions

- Streamlined flow paths: Avoid sharp corners and sudden changes

- Integrated manifolds: Reduce connection losses

Port and Fitting Improvements:

- Larger port diameters: Increase by 25-50% over minimum calculated

- Smooth transitions: Chamfered or radiused entries

- High-quality fittings: Precision-manufactured internal geometries

- Straight-through designs: Minimize flow direction changes

System Design Optimization

Layout Improvements:

- Shorter flow paths: Direct routing between components

- Minimize fittings: Use continuous tubing where possible

- Parallel flow paths: Distribute flow to reduce individual velocities

- Strategic component placement: Position high-loss components optimally

Sizing Guidelines:

- Tubing diameter: Size for maximum 15 m/s velocity

- Port sizing: 1.5-2x minimum calculated area

- Valve selection: Cv rating 2-3x calculated requirement

- Filter sizing: Size for <0.1 bar loss at maximum flow

Advanced Optimization Techniques

| Technique | Pressure Drop Reduction | Implementation Cost | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Port enlargement | 40-60% | Low | Low |

| Valve upgrade | 30-50% | Medium | Low |

| System redesign | 50-70% | High | High |

| CFD optimization | 60-80% | Medium | Very High |

Maintenance and Operational Practices

Filter Management:

- Regular replacement: Before differential pressure exceeds 0.2 bar

- Proper sizing: Oversized filters reduce pressure drop

- Bypass systems: Allow maintenance without shutdown

- Condition monitoring: Continuous differential pressure monitoring

Installation Best Practices:

- Proper alignment: Ensure fittings are fully seated

- Smooth transitions: Avoid internal steps or gaps

- Adequate support: Prevent line deformation under pressure

- Quality control: Inspect internal geometry after installation

Bepto’s Pressure Drop Optimization Solutions

At Bepto Pneumatics, we’ve developed comprehensive approaches to minimize system pressure drops:

Design Innovations:

- Optimized port geometry: CFD-designed flow paths

- Integrated manifold systems: Eliminate external connections

- Large-bore cylinders: Oversized ports for reduced losses

- Streamlined fittings: Custom-designed low-loss connections

Performance Results:

- Pressure drop reduction: 60-80% improvement over standard designs

- Force recovery: 90-95% of theoretical force achieved

- Speed improvement: 40-60% faster cycle times

- Energy efficiency: 25-35% reduction in compressed air consumption

Implementation Strategy for Maria’s System

Phase 1: Quick Wins (Week 1-2)

- Filter replacement: High-flow, low-restriction filters

- Valve manifold upgrade: High Cv directional valves

- Fitting optimization: Replace restrictive push-in fittings

- Tubing upgrades: Larger diameter supply lines

Phase 2: System Redesign (Month 1-2)

- Manifold integration: Custom manifold with optimized flow paths

- Port modifications: Enlarge cylinder ports where possible

- Layout optimization: Redesign pneumatic routing

- Component consolidation: Reduce number of flow restrictions

Phase 3: Advanced Optimization (Month 3-6)

- CFD analysis: Optimize complex flow geometries

- Custom components: Design application-specific solutions

- Performance monitoring: Continuous system optimization

- Predictive maintenance: Pressure-drop-based maintenance scheduling

Results and Performance Improvement

Maria’s Implementation Results:

- Pressure drop reduction: From 2.2 bar to 0.8 bar (64% improvement)

- Available cylinder pressure: Increased from 4.8 bar to 6.2 bar

- Force recovery: From 860 N to 1,160 N (35% improvement)

- Speed improvement: 45% faster cycle times

- Energy efficiency: 28% reduction in air consumption

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Implementation Costs:

- Component upgrades: $15,000

- System modifications: $8,000

- Engineering time: $5,000

- Installation: $3,000

- Total investment: $31,000

Annual Benefits:

- Productivity improvement: $85,000 (faster cycle times)

- Energy savings: $18,000 (reduced air consumption)

- Maintenance reduction: $8,000 (less component stress)

- Quality improvement: $12,000 (more consistent performance)

- Total annual benefit: $123,000

ROI Analysis:

- Payback period: 3.0 months

- 10-year NPV: $920,000

- Internal rate of return: 295%

Monitoring and Continuous Improvement

Performance Tracking:

- Pressure monitoring: Continuous measurement at key points

- Flow rate tracking: Monitor system flow requirements

- Efficiency calculation: Track system performance over time

- Trend analysis: Identify degradation patterns

Optimization Opportunities:

- Seasonal adjustments: Account for temperature effects

- Load optimization: Adjust for varying production requirements

- Technology upgrades: Implement new low-loss components

- Best practices: Share successful optimization techniques

The key to successful pressure drop optimization lies in understanding that every restriction matters, and the cumulative effect of multiple small improvements can dramatically transform system performance. 💪

FAQs About Pressure Drop Dynamics

What percentage of supply pressure is typically lost to pressure drops?

Well-designed pneumatic systems should lose no more than 10-15% of supply pressure to restrictions, while poorly designed systems can lose 30-50%. Systems losing more than 20% of supply pressure should be evaluated for optimization opportunities.

How do you prioritize which pressure drops to address first?

Use Pareto analysis to focus on the largest individual losses first. Typically, valve manifolds and filters contribute 50-60% of total system pressure drop, making them the highest priority for optimization efforts.

Can pressure drop be completely eliminated?

Complete elimination is impossible due to fundamental fluid mechanics, but pressure drops can be minimized to 5-10% of supply pressure through proper design. The goal is to achieve the best balance between performance and cost.

How does pressure drop affect cylinder speed vs. force differently?

Pressure drop affects both force and speed, but the relationships differ. Force decreases linearly with pressure drop (F ∝ P), while speed decreases with the square root of pressure drop (v ∝ √ΔP), making speed less sensitive to moderate pressure losses.

Do rodless cylinders have different pressure drop characteristics?

Rodless cylinders can be designed with larger, more optimized ports due to their construction flexibility, potentially offering 20-30% lower pressure drops than equivalent rod cylinders. However, they may have more complex internal flow paths that require careful design optimization.

-

Review the branch of physics concerned with the mechanics of fluids and the forces acting on them. ↩

-

Understand the phenomenon where fluid detaches from a surface, causing turbulence and energy loss. ↩

-

Explore the dimensionless quantity used to predict flow patterns and the transition from laminar to turbulent flow. ↩

-

Verify the physical constant for dry air used in density and pressure calculations. ↩

-

Learn about the numerical analysis method used to analyze and solve problems that involve fluid flows. ↩